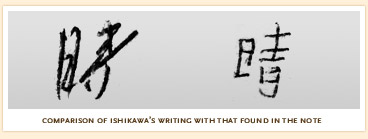

First and foremost, Ishikawa could not have written the ransom note that was delivered to the victim’s family. Like other Buraku people of his generation, he came from an impoverished background and, as a result, he was not well educated. At the time of his arrest, he was 24 years old, lacked even an elementary school education, and was illiterate. The ransom note that was delivered to the victim’s house, however, contained many Chinese characters and was written by a person accustomed to writing. The courts maintain that Ishikawa could have copied the Chinese characters out of a magazine, but analysts have testified that the handwriting is clearly that of a different person. There is also no evidence of Ishikawa’s fingerprints on the ransom note or on the envelope it was in.

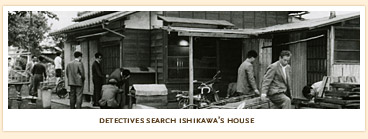

In addition to Ishikawa’s forced confession, the court has based much of its decision on the fact that the victim’s pen was found at Ishikawa’s house. However, this fountain pen was not discovered until the third search of his residence. On May 23, the day Ishikawa was arrested, the police came to his house, woke him up and took him to jail. Twelve detectives conducted a full, two-hour search of the premises. They took several objects from as potential evidence, but did not find the victim’s pen. On June 18, a second search of the premises was conducted. Fourteen detectives participated, specifically looking for the victim’s bag, watch, and pen. They searched the entire premises for over two hours but found nothing.

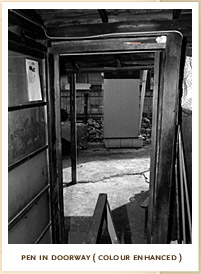

Eight days later, following these two extensive searches by a total of 26 trained detectives, the pen was found on the doorframe in Ishikawa’s kitchen. Both court decisions, that of the Tokyo High Court and the Supreme Court, state that the first 26 detectives had simply overlooked the doorframe, but their reasons for why this happened differ. The Tokyo High Court said that it was because the location was too obvious, while the Supreme Court maintained that short people would have difficulty seeing the top of the doorframe. The doorframe is approximately 1.83 meters (6 feet) tall; there is a picture of the kitchen taken immediately following the second search that shows a small stepladder in front of the door.

A veteran police detective has testified that it is unthinkable that trained police investigators would have overlooked a bright pink pen on a relatively low doorframe, and even more unthinkable that such a thing could happen twice. The investigators called to search Ishikawa’s house were the top professionals from the area. By the time Ishikawa was arrested, the case had already become a scandal, and the police were doing whatever it took to find the culprit. They spared no cost or personnel in conducting as thorough a search as possible. Furthermore, the doorframe is mentioned in all standard police detective textbooks as a routine location to search.

The prosecutor’s case rests primarily on the confession extracted from Ishikawa while he was in police custody. However, this confession is filled with statements that violate commonsense and do not match the physical layout and characteristics of the crime scene. These discrepancies, in addition to raising reasonable doubt as to whether Ishikawa actually committed the crime, also raise questions about how ‘confessions’ are drafted under the Japanese criminal justice system.