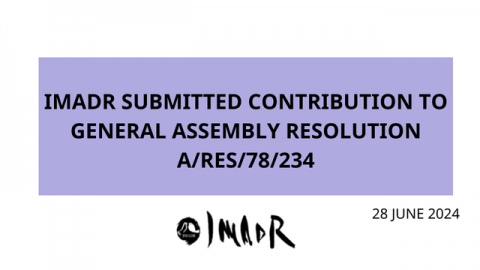

IMADR Submitted Contribution to General Assembly Resolution A/RES/78/234

July 3, 2024

IMADR submitted inputs for General Assembly Resolution A/RES/78/234. Despite the Durban Declaration and Programme of Action (DDPA) to combat racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance at a global level, such racially-motivated acts have been rising in many societies, affecting every aspect of life. Therefore, the purpose of this input is to inform the preparation of the 2024 report of the UN Secretary-General on the implementation of the UN General Assembly resolution A/RES/78/234 that will be presented to the 79th session of the UN General Assembly.

GENERAL ASSEMBLY RESOLUTION A/RES/78/234 “A GLOBAL CALL FOR CONCRETE ACTION FOR THE ELIMINATION OF RACISM, RACIAL DISCRIMINATION XENOPHOBIA AND RELATED INTOLERANCE AND THE COMPREHENSIVE IMPLEMENTATION OF AND FOLLOW-UP TO THE DURBAN DECLARATION AND PROGRAMME OF ACTION”

28 June 2024

INTRODUCTION

The International Movement Against All Forms of Discrimination and Racism (IMADR) is an international non-profit, non-government human rights organisation devoted to eliminating all forms of discrimination and racism, forging international solidarity among discriminated groups and advancing the international human rights system. IMADR appreciates that the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) offers the opportunity to contribute to the development of the report of the UN Secretary-General in accordance with the UN General Assembly resolution (A/RES/78/234). Our submission provides inputs, responding to several guided questions.

HATE SPEECH AND INCITEMENT TO RACIAL DISCRIMINATION

Hate speech is rampant in Japan, especially on the Internet. A prominent case is where a female politician repeatedly wrote racist statements in her blog or on social network services, and incited racial hatred among her supporters. It started in February 2016 when CEDAW considered the State Report of Japan at its 63rd session. There, minority women from Buraku, Ainu indigenous and resident Korean communities joined the session to voice up against intersecting forms of discrimination they faced. She, who was not a member of Parliament at the time, attended the review with her colleagues who supported the history revision. The blog article contained spy photographs of minority women with texts ridiculing and deriding them as ‘customed ants’ or ‘having a problem of dignity’. She posted the same article on social network services. The effect of such incitement to racism by a series of posts has been tremendous, and the minority women concerned have been exposed to the risk of serious discrimination driving themselves in keeping silent. During the 210th Extraordinary Diet Session in 2022, she, as an MP and a Parliamentary Secretary at the time, was questioned about these words and actions by other MPs several times in the different Parliament committees. Yet, she never admitted that what she had done constituted hate speech inciting hatred against these women. Instead, she kept saying, “I hurt people with my poor expressions” and “It was conveyed as if I had discriminated”.

The prime minister as well as the Minister of Justice failed to admit it as “hate speech” or “racial discrimination” despite the fact that Japan is bound by the ICERD, to be specific by its Article 4 © that stipulates “shall not permit public authorities or public institutions, national or local, to promote or incite racial discrimination.” After all, she voluntarily resigned as the government position as a Parliamentary Secretary, not the dismissal by the Prime Minister. She still holds her seat in the Parliament.

SYSTEMIC RACISM

The Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, which is the ministry in charge of education policy of the State party, has not been willing to work on solving the problem even after receiving the concluding observations of the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination in August 2018[1]. Japanese schools have the positions of principal, vice-principal, chief teacher, teacher, and instructor. However, foreign teachers in public schools can only take the position of instructors at the bottom. This is because foreigners are excluded from the positions of principal through teachers. Japanese citizens are hired as teachers if they pass the teacher employment examination. After being hired, it is possible to be promoted to the principal. On the other hand, even if a foreigner gains a teacher’s license and even passes the teacher employment examination like a Japanese citizen, they can only be appointed as instructors and will remain in this position until retirement, and cannot be promoted.

It is estimated that 300 or more ethnic Koreans in Japan and other foreign nationals hold teaching jobs in public schools across Japan, but the difference between the lifetime earnings of a person who remains an instructor and one who rises to the position of principal is said to be 10 to 20 million yen (approx. USD65,000-130,000). In this way, foreign faculty members are placed at a financial disadvantage. The Government of Japan insists that “public servant positions involving the exercise of public authority or participation in public will formation are restricted to Japanese nationals” [2], but this is not based in law. The government’s claims that this is a “natural matter of course”, is equivalent to saying that it is “natural” to discriminate against foreigners. Article 4 of the Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights states, “…the State may subject such rights only to such limitations as are determined by law…”, but the Government of Japan violates the rights of foreigners by administrative notices, etc., regardless of the law.

The Government of Japan is dragging in the present the same state-controlled education system of the militaristic era before the defeat of Japan in 1945. It is thought that there is an idea that only teachers who are national citizens can perform educational activities in the execution of nationalist education. Similarly, foreign teachers are considered to be an obstacle in promoting education that respects the imperial family, fosters patriotism, and fosters children who pledge allegiance to the nation. Therefore, foreign teachers are only assigned to the lowest-rung jobs in school education.

Historically, when the San Francisco Treaty was concluded in 1952, it allowed Japan to deprive people of formerly colonised countries by Japan of their Japanese citizenship. Then, people who had already been public officers, including teachers, were forced to naturalise. For those who denied naturalisation, the government expressed its view that public officers need Japanese citizenship. Such systemic racism rooted in colonial history has a hand in the reproduction of unequal relationships and excluding attitudes towards ‘foreigners’.

CHILDREN AND YOUTH OF AFRICAN DESCENT

Hairstyle and hair texture are influential factors that children and youth of African descent face discrimination at school. In February 2023, a ninth-grade male student of African descent was not able to attend the graduation ceremony owing to his cornrow hairstyle which was, according to the school, against school rules[3]. He was ordered to sit on the second floor, isolated from other students, and prohibited from responding when his name was called. Then, he and his family decided to leave in the middle of the ceremony since there was no point in being at it.

Concerning the reason why he could not join the ceremony as other students did, the deputy headteacher repeatedly states “he should know the rule” when his parents asked. The school’s rule stipulates that the hairstyle should be ‘clean and appropriate for a high school student’ without prohibition on cornrow hairstyles. Underlyingly, there is the idea that straight hair is cleaner and more appropriate for students than curly hair, which was shared among teachers. Hairstyles are intertwined with hair texture. Cornrow hairstyles is used mostly by people of African descent to tighten their curly hair. That hairstyle is considered ‘clean’ and ‘appropriate’ for a ceremony in their cultural context. Since hair is not just a hair and it shows one’s identity and culture, denying it hurt the dignity of students of African descent as illustrated by the student saying “I felt to be told that it was not special day to me. The hairstyle is my father’s roots and my culture as a person of African descent” [4].

The prohibition of certain hairstyles has been a problem regardless of their racial or national origin in Japan[5]. It is not rare for Japanese schools to have teachers and/or school rules that prohibit hair in buns, braided hair, two-block hair, ponytails and among other hairstyles as well as that do not acknowledge curly hair. Such attitudes towards hair are internalised by students and students with curly hair are more likely to be a target of bullying. In this way, the idea of straight hair as better is normalised and reproduced, marginalising or discriminating people without straight hair.

However, that has a racial aspect. As illustrated by the incident above, the attitude towards certain hairstyles interweaved hair texture that is natural to a student’s racial origins might disseminate negative stereotypes or prejudices in relation to their race. Moreover, it lowers the self-esteem of students, who are also in a sensitive adolescent period, hurts them and (re)produces a vicious circle. In these ways, students of African descent experience racial discrimination on the grounds of their hair texture and hairstyles.

[1] CERD/C/JPN/CO/10-11, para.22, 34(e)

[2] CERD/C/JPN/CO/10-11, para.81

[3] https://mainichi.jp/articles/20230327/k00/00m/040/127000

[4] Ibid